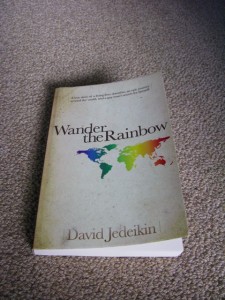

Getting this book out has been almost a bigger adventure than the trip it chronicles – and I don’t mean just writing it.

Getting this book out has been almost a bigger adventure than the trip it chronicles – and I don’t mean just writing it.

As some of you may know, I’m also handling all the publishing work – in fact, this was one reason I chose to embark on this foray in the first place: Until recently, it was near-impossible to get published unless you embarked on the long, tortuous path of finding an agent, a publisher, and a book deal.

But now the Internet’s changed all that.

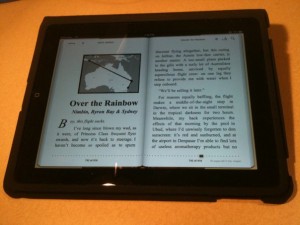

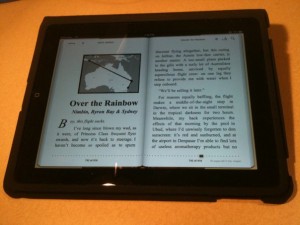

The most obvious upheaval in publishing-land is the arrival of the e-book. Just as MP3s supplanted CDs and now MP4s look to be replacing DVDs, so too has much been said (and written) about the transformation of the printed-matter business to a digital model. Specifically, the e-book, readable on a range of miniature devices – Amazon’s Kindle, Barnes & Noble’s Nook, Sony’s Reader, and, of course, Apple’s venerated iPad. Most of these try to make the computer-screen experience as book-like as possible, from non-luminous “e-ink†screens to lengthy battery life to page-flip animations. Their popularity is growing, with speculation that they could capture up to a quarter of the book market within two years (currently their share is under 10%).

For independent publishers, this represents an opportunity: freed of the need to deal with printing and distribution logistics, suddenly anyone can become a publisher with minimal start-up and distribution costs. Quite a number of authors are making their work available this way, often for a fraction of the cost of conventionally published books.

That’s all well and good for those who own Kindles or iPads or some other device… but what about the rest of us?

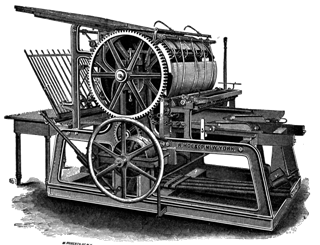

Enter the world of “print on demand.â€

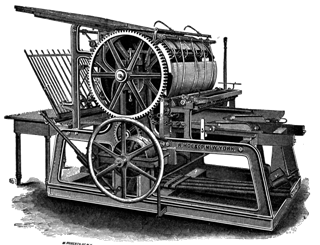

Conventional modern printing presses (known as offset presses) are most suitable for large print runs: In the thousands, tens of thousands, or more. Coupled with the high cost of owning and maintaining these machines, traditional printing has always been a large-scale, typically corporate endeavor (unless you were one of those “vanity publishers†who paid large sums to see a work in print, most often after having been rejected by mainstream publishers). But nowadays, with new printing technologies going hand-in-hand with evolutions in computer software, it’s become possible to produce a competitively-priced, high-quality printed book “on demand†– a single copy, or five, or 500. Coupled with the ability to sell on sites like Amazon, Barnes & Noble.com, and others, the traditional bricks-and-mortar hammerlock on book publishing has begun to erode.

That all sounds great – if only it was that easy!

Like DIY home remodeling (which I’ve done as well), indie publishing means doing it all yourself; all those new software and printing technologies translate into a bewildering array of formats, style rules, and procedures that – I can now say having been through the wringer myself – are not for the faint of heart (or the technically challenged).

I did a stint in advertising print production some years back, so the vagaries of CMYK color spaces and pre-press output aren’t too unfamiliar. This enabled me to wear my production coordinator hat to ensure everything – interior, cover art, all the way down to the little section divider icons – looked its best… though I’d be remiss if I didn’t include a shout-out to my editor, Elsa Dixon, and my proofreader, Palmer Gibbs. They found mistakes and omissions I never would have. Great job guys!

I did a stint in advertising print production some years back, so the vagaries of CMYK color spaces and pre-press output aren’t too unfamiliar. This enabled me to wear my production coordinator hat to ensure everything – interior, cover art, all the way down to the little section divider icons – looked its best… though I’d be remiss if I didn’t include a shout-out to my editor, Elsa Dixon, and my proofreader, Palmer Gibbs. They found mistakes and omissions I never would have. Great job guys!

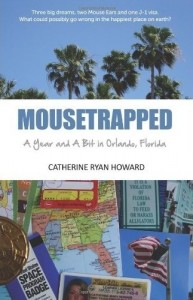

Beyond the specifics of print, however, I also had to learn a whole new language of publishing: ISBNs, publisher of record, rights clearances… you name it. For you fans of travel and philosophy writer Alain De Botton, his publishers (both U.S. and worldwide) granted permission (for a nominal fee) to reprint an excerpt from one of his books, The Art of Travel.

With the print copies squared away, I then set upon converting everything to digital formats. Should be easy, I mused, for someone like myself with a technology day job. Plus everything was already nicely formatted for print, so how hard could it be?

The still-emerging e-book world threatens to upend the way we think of books on many levels. When creating content destined for e-readers, a number of presentation paradigms vanish: The page, for one. Oh sure, all e-readers display text on a screen made to look like a page – the iPad even offers animation to give the illusion of flipping pages. But unlike pages destined for print – which are laid out and spaced precisely to fit exact dimensions (in the case of Wander the Rainbow, 6†x 9†paperback), e-pages must be “re-flowable.â€

Huh?

This means that the text can be resized by the reader. This nice bit of functionality means the traditional concept of a “page†is no longer relevant – a page is simply whatever fits on the reader’s screen at the typeface size they choose. An e-book document, therefore, needs to be infinitely flexible – and look good at all those different sizes.

Making matters more interesting is that bugaboo all too familiar to techies: the format war. Just like Beta and VHS, and HD-DVD and Blu-Ray, the different e-readers use a number of different – and incompatible – file formats. Amazon’s Kindle, the most popular reader out there, uses its own format. Apple’s iPad, Sony’s Reader, and Barnes & Noble’s Nook use the more standard ePub format. They’re all pretty similar – they use the standard language of the Web, HTML, to specify text and image placement. But subtle differences over 312 pages and thirty-plus chapters meant a sizeable conversion effort. Oh sure, there’s software out there to automate this for you, but much of it is designed for home users to convert their own documents across the different formats – appearance be damned. There was no way I would shortchange my digital readers by giving them a less-than-printed-book-quality experience… which meant a few late nights of painstaking, chapter-by-chapter conversion.

Making matters more interesting is that bugaboo all too familiar to techies: the format war. Just like Beta and VHS, and HD-DVD and Blu-Ray, the different e-readers use a number of different – and incompatible – file formats. Amazon’s Kindle, the most popular reader out there, uses its own format. Apple’s iPad, Sony’s Reader, and Barnes & Noble’s Nook use the more standard ePub format. They’re all pretty similar – they use the standard language of the Web, HTML, to specify text and image placement. But subtle differences over 312 pages and thirty-plus chapters meant a sizeable conversion effort. Oh sure, there’s software out there to automate this for you, but much of it is designed for home users to convert their own documents across the different formats – appearance be damned. There was no way I would shortchange my digital readers by giving them a less-than-printed-book-quality experience… which meant a few late nights of painstaking, chapter-by-chapter conversion.

I think the results are worth it – some preliminary tests on co-workers’ iPads and Sony Readers (one plus about working in tech: somebody in your circle is bound to be on the bleeding edge) completed the process – as did the arrival of the final proof just last week. Well, almost: As of last Thursday the proof was somewhere in limbo, having been sent USPS Express Mail… who had no record of their own tracking number or any idea where the package was. Finally it showed up (mysteriously with a UPS label on it – something tells me it needed to be re-sent behind the scenes) and looked grand.

Tags: