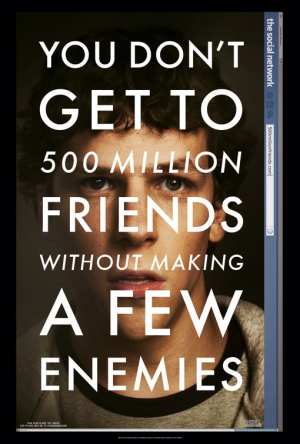

What The Social Network has to teach us about friendship, business, and the American Dream

If there’s one thing a long trip helps to sharpen and clarify, it’s one’s notions (and occasional frustrations) about life back home. Although not everyone utterly rejects and abandons their homeland, time away definitely induces one to notice the warts & all you leave behind.

This was on my mind as I watched The Social Network, the Aaron Sorkin-penned (The West Wing), David Fincher-directed (Se7en, Fight Club, Zodiac, The Curious Case of Benjamin Button) story of the founding of Facebook. For the uninitiated, the monstrously successful social network (500 million-plus users and an estimated valuation of over $11 billion) had messy origins, replete with student-life melodrama and big-money lawsuits as it climbed to the top of not only the social-networking heap (remember MySpace? Friendster?) but to the pinnacle of the web overall — it’s the number-two ranked site on the entire Internet, and its co-founder and CEO, Mark Zuckerberg, is the youngest billionaire in history.

I didn’t go to Harvard and I’m not a billionaire web entrepreneur, but so much of this film spoke to me: the social awkwardness of being a geek in college; the rush of excitement and raw emotion that accompanies youthful business endeavors; the fallout and reprisals between friends and lovers. Zuckerberg (played by Jesse Eisenberg) comes across as icy and arrogant — but he’s so unbelievably similar to many hyper-smart outsider tech geeks that I don’t consider the portrait all that unflattering. In my own past I’ve had run-ins with collegate political correctness and the intransigence of university officials. On those levels, I get you, Zuck (as the real-life Facebook founder is known).

But what echoed most deeply about the story is the ever-present competitiveness and money/power-grabbing that underlies the Facebook enterprise and the power centers where it is situated: America’s elite academic center (Boston/Harvard), its media center (New York, sidelined in the story as Facebook finds only modest success in securing early-stage advertisers) and its technology center (the San Francisco Bay Area). I’ve remarked for years how the Bay Area in general and San Francisco in particular have morphed from once-sleepy hippie spots to the center of America’s most prestigious and visible industry. This movie nails it, as Sean Parker (played by Justin Timberlake), the partying, manic, glitzy Napster co-founder, seduces Zuck to the capitalist dark side with promises of venture funding and ultimate billions (both of which have since come true) at a San Francisco nightclub.

Like the fictional Charles Foster Kane before him, Zuckerberg makes the ultimate business choice: he sidelines his more cautious best friend Eduardo Saverin (played by Andrew Garfield) and his incremental business plans in favor of the growth-and-glory-obsessed Parker — just as Kane did to his best friend Jedediah Leland in Orson Welles’ movie. Earlier on, Zuckerberg blows off old-money Harvard twins Tyler and Cameron Winklevoss and their plans for a social network of their own. Just like Kane and Rosebud (his sled, which represented the simple, modest life he left behind), Zuck leaves all these guys and their moderately-winning schemes in the dust in pursuit of epic, huge-time success.

But just as Kane posited, so too this movie: what serious go-getter in our present-day capitalist age– an era where the U.S.A. acts as standard-bearer — wouldn’t make these choices? In my early days in this country I called it the American Nightmare — the dark side of the American Dream that compels anyone with an opportunity to take it and run with it to its greatest, most successful end, sometimes at the expense of your nearest and dearest.

Ironically, as both films show, those titans of industry who’ve been so instrumental in making our lives easier, more comfortable, or more connected suffer from an inability to truly connect with others: Kane tries to collect artifacts but cannot win the hearts of an electorate or the heart of his two wives; Zuck, at the end of the film, finds the girl who dumped him at the start of the story — on Facebook, natch — where he sends her a friend request and sits there, refreshing the page over and over, waiting for a response. The young man who connected so many millions remains, at heart, a loner.

Tags: