Okay, time for a day off.

Okay, time for a day off.

This statement is a toughie for some of us on vacation, especially on shorter trips where we feel compelled to maximize our time. But it’s something I learned to do on my big world trip, and can attest to its powers to enhance almost any kind of holiday.

So what the heck was I going to do in a ski town if I wasn’t skiing (or boarding)?

A bit of shopping, for one: yes, it is possible to find not-too-expensive gifts for nears-and-dears in this place… and they don’t all involve chocolate. Oh, who am I kidding; I bought a pile of that as well.

Fraternizing with the natives, for another. Zermatt’s not much of a gay destination (though come to think of it, I haven’t found snow resorts anywhere to be so), but I had had some success chatting online with a smattering of fellows. I was halfway to putting on my snow gear and opting for an easy half-day on the slopes when one guy I’d been talking to messaged me; he was off work today and was up for a rendezvous.

We met around the corner from my hotel, outside the church in Kirchplatz. Jan was fair-featured and athletic, hails from Interlaken and has been working for the season at the restaurant in the classiest spot in town, the Grand Hotel Zermatterhof. The quaver in his voice indicated he was interested in more than just a chat.

We met around the corner from my hotel, outside the church in Kirchplatz. Jan was fair-featured and athletic, hails from Interlaken and has been working for the season at the restaurant in the classiest spot in town, the Grand Hotel Zermatterhof. The quaver in his voice indicated he was interested in more than just a chat.

“It’s not so nice,” he said of his gorgeous, $800-a-night workplace. Lordie, not another one. It seems that faux-jaded gay youth are a constant the world over. This translated into an equally tepid performance back at my hotel room. It was all over in less than fifteen minutes as he put his clothes back on.

“I hate the spa,” he said, when I asked him about where in town I should go if I wanted a dunk in a jacuzzi somewhere. “And if you find one, it will cost you at least 75 Francs.”

“Really?” That’s north of 80 Yankee bucks.

“Welcome to Switzerland,” he replied, as he headed off. The whole thing felt like one of those furtive gay encounters you read about from the Mad Men 1960s. Heck, I’m all for casual encounters, but call me a romantic as I prefer even those to retain a measure of intimacy and warmth. Oh, well. Still not too bad for a day off.

It was too late to head out on the slopes, so I opted for more cultural offerings: right by my hotel was the newly-built Matterhorn Museum. In spite of its name, it’s really more a historical exhibit on Zermatt tiself – which suited me just fine. I’m curious to the point of obsessive about how places came to be the way they are; some have criticized Wander the Rainbow for delving a bit too heavily into factoids cribbed from Wikipedia, but in truth, the discovery of a place’s origins and evolution ranks near the top of my travel interests.

It was too late to head out on the slopes, so I opted for more cultural offerings: right by my hotel was the newly-built Matterhorn Museum. In spite of its name, it’s really more a historical exhibit on Zermatt tiself – which suited me just fine. I’m curious to the point of obsessive about how places came to be the way they are; some have criticized Wander the Rainbow for delving a bit too heavily into factoids cribbed from Wikipedia, but in truth, the discovery of a place’s origins and evolution ranks near the top of my travel interests.

Surprisingly, for a place so world-renowned, I hadn’t been able to find out a whole lot about Zermatt or this region among my usual suspects of online research sites. Maybe because snow enthusiasts aren’t terribly interested in the vagaries of ski-resort history; indeed, most resorts Stateside have a fairly straightforward past: either they began life as rugged mining towns that transformed themselves mid-20th-century into ski towns (Aspen, Breckenridge); or else were synthesized out of whole cloth to mimic alpine resorts in the Old World (Vail, Whistler).

But Zermatt’s another story entirely. Humans have been passing through the nearby Theodul Pass for eons. Neolithic tools, Roman coins, and remains of a 16th-century man have all been found nearby. With the advent of Europe’s Little Ice Age in the later Middle Ages, however, traffic slowed as the Simplon and Great St. Bernard passes rose in prominence. By the middle of the 19th century, Zermatt was a poor farming village filled with those now-iconic wide-sloped-roof Swiss chalets. I learned why these wood-framed structures (some specimens from way back lay across from my accommodations) sit on stone stilts: used for agricultural storage, they needed to protect themselves from prying mice.

But Zermatt’s another story entirely. Humans have been passing through the nearby Theodul Pass for eons. Neolithic tools, Roman coins, and remains of a 16th-century man have all been found nearby. With the advent of Europe’s Little Ice Age in the later Middle Ages, however, traffic slowed as the Simplon and Great St. Bernard passes rose in prominence. By the middle of the 19th century, Zermatt was a poor farming village filled with those now-iconic wide-sloped-roof Swiss chalets. I learned why these wood-framed structures (some specimens from way back lay across from my accommodations) sit on stone stilts: used for agricultural storage, they needed to protect themselves from prying mice.

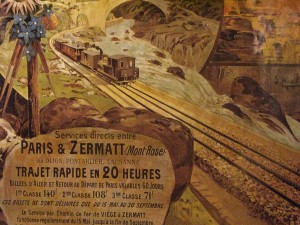

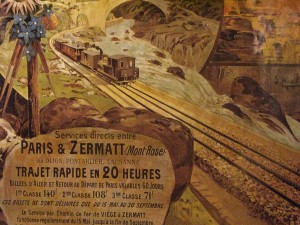

So what transformed this sleepy farming hamlet into an elite class resort? Blame it on those Victorian Brits and their zeal to take on the world. This I learned about at my next stop, the nearby Hotel Monte Rosa, the oldest of the town’s high-end accommodations. In a walking tour and talk delivered by a prim young blonde hotel staffer – in near-effortless German, French and English – I learned that the so-called Golden Age of Mountaineering drew British climbers to this spot. The Matterhorn was one of the later peaks to be scaled in the region, and its summiteer, Edward Whymper, left from this very hotel in 1865. In spite of a successful climb, four people were lost in that endeavor and it became something of a scandal in the British press. Notoriety bred curiosity, however, and soon people were flocking to this isolated Swiss village. The Monte Rosa expanded several times; its owner, Alexander Seiler, became a local magnate with ownership of the lion’s share of the town’s hotels (though as a pushy entrepreneur he received a frosty reception from the town’s burghers). Rail links to Visp and up the Gornergrat followed by the end of the 19th century, though it was only after the turmoil of the World Wars and the ascendancy of winter sports that the town took on its high-tone appeal.

So what transformed this sleepy farming hamlet into an elite class resort? Blame it on those Victorian Brits and their zeal to take on the world. This I learned about at my next stop, the nearby Hotel Monte Rosa, the oldest of the town’s high-end accommodations. In a walking tour and talk delivered by a prim young blonde hotel staffer – in near-effortless German, French and English – I learned that the so-called Golden Age of Mountaineering drew British climbers to this spot. The Matterhorn was one of the later peaks to be scaled in the region, and its summiteer, Edward Whymper, left from this very hotel in 1865. In spite of a successful climb, four people were lost in that endeavor and it became something of a scandal in the British press. Notoriety bred curiosity, however, and soon people were flocking to this isolated Swiss village. The Monte Rosa expanded several times; its owner, Alexander Seiler, became a local magnate with ownership of the lion’s share of the town’s hotels (though as a pushy entrepreneur he received a frosty reception from the town’s burghers). Rail links to Visp and up the Gornergrat followed by the end of the 19th century, though it was only after the turmoil of the World Wars and the ascendancy of winter sports that the town took on its high-tone appeal.

With that history lesson completed, I sought some relaxation; proving Jan decidedly wrong, I headed to the Mont Cervin Palace, the third of the town’s ritzy hotels, and for a modest sum whiled away the rest of the afternoon in their beautiful health club: two jacuzzis, a standard swimming pool, and a heated indoor/outdoor pool proved an excellent tonic.

With that history lesson completed, I sought some relaxation; proving Jan decidedly wrong, I headed to the Mont Cervin Palace, the third of the town’s ritzy hotels, and for a modest sum whiled away the rest of the afternoon in their beautiful health club: two jacuzzis, a standard swimming pool, and a heated indoor/outdoor pool proved an excellent tonic.

To cap it all off, another iconic Swiss dish was in the offing: the nearby Café du Pont was widely recommended as among the best (and one of the more reasonable – though not cheap) spots to enjoy cheese fondue. Impressively, they even did it for my “table for one.”

As it grew later I received a message from another guy online: Pascal was getting off work late, around 11 p.m., but was open to a meetup after that. I wasn’t sure what to expect after my previous encounter, but something about the style of his messages gave me hope. I met him, too, outside the church close to midnight, and indeed, he was a total contrast from the previous encounter.

“I came here to visit a friend five years ago, and I loved it so much!” said Pascal. About the same age as Jan but way more gregarious, engaging, and positive. He took me for a drink at a nearby lounge-y spot where, apparently, the town’s few gays often congregate.

“There are maybe ten in the whole town,” he said. “They are mostly arrogant and not very nice.” Tell me about it. Happily, he proved different: we had a wonderful chat about life in Europe (he hails from western Germany, not far from Luxembourg), politics in America, the ski season, and myriad other events. He, too, came back with me, and this go-round was a damn sight better than the last one. I hit the pillow around 2 a.m. on an Alpine mountain high.

In spite of the late night, I rose on my own steam bright and early for a final day on the slopes. A bit of light snow had fallen the day before, but now skies were blue again, albeit with tendrils of cloud hugging and swirling about the mountains. I again did the gondola/cable car combo to the top of Klein Matterhorn; this time it was windier, colder, and less crowded. As I began my descent, I whooshed into some clouds and it began to snow. The dense fog meant whiteout conditions. But, as with fog back in San Fran, the murk shortly cleared and I opted for another far-flung adventure: taking the pistes all the way down to the other base resort on the Italian side: the town of Valtournenche.

In spite of the late night, I rose on my own steam bright and early for a final day on the slopes. A bit of light snow had fallen the day before, but now skies were blue again, albeit with tendrils of cloud hugging and swirling about the mountains. I again did the gondola/cable car combo to the top of Klein Matterhorn; this time it was windier, colder, and less crowded. As I began my descent, I whooshed into some clouds and it began to snow. The dense fog meant whiteout conditions. But, as with fog back in San Fran, the murk shortly cleared and I opted for another far-flung adventure: taking the pistes all the way down to the other base resort on the Italian side: the town of Valtournenche.

This was the longest descent yet, as Valtournenche lies at an even lower elevation than Zermatt. But I paced myself this time, carefully navigating a couple of traverses and a mini-chairlift to get to the other side of this massive set of mountains. Here again, a narrow trail to the bottom, and, with the low elevation (1,524 m, about the same as Salt Lake City), mushy spring conditions and bare slopes all around us.

This was the longest descent yet, as Valtournenche lies at an even lower elevation than Zermatt. But I paced myself this time, carefully navigating a couple of traverses and a mini-chairlift to get to the other side of this massive set of mountains. Here again, a narrow trail to the bottom, and, with the low elevation (1,524 m, about the same as Salt Lake City), mushy spring conditions and bare slopes all around us.

Valtournenche, too, wasn’t much of a place, so I hopped the gondola up to one of the Italian mountain eateries and had myself a seafood pasta, one of the better insalata caprese in my career, and (of course) a most righteous cappuccino on the sunny slopes.

Thus fortified, I embarked on my next adventure: getting back to Zermatt.

Thus fortified, I embarked on my next adventure: getting back to Zermatt.

Given what I’d experienced so far, this ought have been a breeze. The resort is, as I’d mentioned, richly endowed with high-tech lifts to get around its mammoth acreage. On the first two days, between the cog railways, funiculars, gondolas and aerial trams, I never once planted my butt on something as prosaic as a chairlift.

No more, as the Valtournenche side isn’t quite as blessed. Aside from the minor nuisance of sitting out in the cold, however, to most skiers the reaction this would be a ho-hum “so what?” But a snowboard, admittedly a less practical conveyance, is trickier to navigate on fast-moving, ski-on/ski-off lifts. One of the toughest elements, in fact, in learning the sport is simply getting on and off chairlifts – and klutz that I am, I still fall a percentage of the time on descent.

But the chairlifts were not the issue (especially since some of them had enclosed bubble canopies to ward off the chill – why this had not been thought of years ago is beyond me). No, looking on the trail map, my heart sank:

The only way to get back to Zermatt from Valtournenche was to take a rope tow, also known as a Poma lift. This contraption – one of the earliest to ferry skiers up an incline – has the passenger sit on it on the ground while it pulls them forward; essentially, it’s like skiing uphill. Suffice it to say, it’s a nightmare on a snowboard; I’d tried riding some of these throughout my years as a snowboarder, and every time I’d fallen off midway, having to haul myself through deep powder to a nearby trail, panting and exhausted by the end. I was dreading this, but steeling myself for the inevitable all the same: if I fall off, I’ll just try it again, I mused.

The only way to get back to Zermatt from Valtournenche was to take a rope tow, also known as a Poma lift. This contraption – one of the earliest to ferry skiers up an incline – has the passenger sit on it on the ground while it pulls them forward; essentially, it’s like skiing uphill. Suffice it to say, it’s a nightmare on a snowboard; I’d tried riding some of these throughout my years as a snowboarder, and every time I’d fallen off midway, having to haul myself through deep powder to a nearby trail, panting and exhausted by the end. I was dreading this, but steeling myself for the inevitable all the same: if I fall off, I’ll just try it again, I mused.

Just as I got to the Lift of Death, I saw in line ahead of me an affable young British couple, the only other ones braving this thing on snowboards.

“How do you ride this thing?” I asked them.

“Just stay loose,” they replied, showing me how as the lift attendent placed the round red seat between their legs. I was next, and he did the same with me. I got in the typical “skate” position (one leg bolted to the board, another not), and…

“Just stay loose,” they replied, showing me how as the lift attendent placed the round red seat between their legs. I was next, and he did the same with me. I got in the typical “skate” position (one leg bolted to the board, another not), and…

Hey, I can do this!

I rode all the way to the top, and once there let out a victorious whoop. I’d been sensing that my skills as a snowboarder had grown surer in my time here on the massive slopes, and if nothing else, this was vindication of that.

By the time I’d reached the top of Plateau Rosa, on the Swiss/Italian border once more, skies had mostly cleared save for a few remaining wisps swirling about the mountains. Unlike the previous day, I was feeling assured and ready for the final run into Zermatt. I began heading down the mountain, the glorious Matterhorn again resuming its oft-photographed form. I parked myself on a quiet trail and stared at it for a spell.

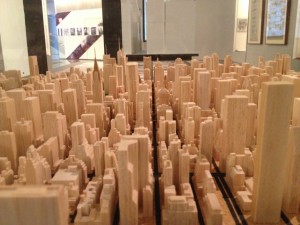

It’s all small stuff, I mused, about the myriad stressors and ups and downs in my life of late. Sometimes it takes a week or so of staring a glorious scenery to remind one of the bigger picture. I turned back toward Zermatt – still toylike down in the valley below – to call it an afternoon.

It’s all small stuff, I mused, about the myriad stressors and ups and downs in my life of late. Sometimes it takes a week or so of staring a glorious scenery to remind one of the bigger picture. I turned back toward Zermatt – still toylike down in the valley below – to call it an afternoon.

And then, just as I’d found inner peace, and all was well with the world, the other shoe dropped. Literally, in fact.

Once more reaching the lower elevations, the trails became narrow, of modest pitch, and a bit icy. Perhaps sensing this, skiers and riders began to pick up their game: where before they floated down the mountain, now they powered down it. No problem, I thought. With my newfound skills and confidence (I rode up a Poma!) I figured I could do so as well. I amped up my usual methodical style, and whooshed down the hill like a pro. And then…

WHAM!

It all happened so quickly, as it so often does: my board caught an edge on the hard-packed snow and I went tumbling, end over end, finally falling hard on my back. My worst fall this trip by far.

It all happened so quickly, as it so often does: my board caught an edge on the hard-packed snow and I went tumbling, end over end, finally falling hard on my back. My worst fall this trip by far.

I wasn’t hurt, aside from a slightly sore butt; I’ve learned to take no chances in snowsports, and I ride the pistes with wrist guards and protective shorts that include a tailbone guard (my nine-year-old niece Lola calls it my “special underwear.”). I also equip myself with one of those Camelbak daypacks that includes an insulated water bladder – much needed at altitude with these exertions. As I’d landed on the pack, my fall was cushioned. Still, I’d heard a tiny crack when I slammed my back on the snow, and instantly knew what it was.

Oh, shit. I thought. My camera.

Taking electronics up and down ski slopes probably sounds like asking for trouble. Still, it’s a risk I’ve opted to take in exchange for capturing the jaw-dropping vistas for myself. Much has been said and written about the notion of actually just experiencing travel instead of constantly trying to capture it… but for me, documenting is part of the experience. That’s why I keep this blog, why I wrote Wander the Rainbow, why I take photographs at times like some stereotypical Japanese tourist. Chronicling my adventures are an integral part of my adventures. Perhaps it’s my background in communications or my love of movies, but I can’t imagine travel without it.

Making sure I was on a spot on the trail where I was clearly visible to the skiers and riders above, I opened my pack and took out the camera. It was embedded inside a scarf and myriad other padding, and thus far looked okay. I turned it on. Still okay… but the lens expanded out all the way out, froze in place, then the screen read: “lens error.” Fuck. It’s one of those higher-end Canon point-and-shoots with interchangeable lenses, so I tried unscrewing the lens – and pieces of the assembly fell into my gloved hands. The camera’s four years old and has already been with me on many outings (including my global circumnavigation), so the loss of it (or the need for a costly repair) may be hurt a little but not a lot. I gingerly put the pieces back in my pack and make ready to resume the ride into town.

“YOU FUCKING IDIOT, WHAT’RE YOU DOING!??” came a cockney-accented voice whooshing past. A gaggle of skiers and riders roared by, one of them obviously enraged that I caused him to slow. Indeed, the trail does feature flat bits that need to be negotiated at some speed (part of the reason for my fall), but up ahead, it wasn’t too bad. I suspected, with the day ending and the trail narrowing, flattening, and icing up, that the crowd has turned more belligerent. Still, I wondered, in the midst of all this glorious scenery, was that really necessary?

I head toward the bottom, more gingerly than before. At one particularly flat, narrow bit of trail I gathered some speed – only to see a pile of skiers sitting down, blocking the trail far worse than I had earlier. I tried to navigate around them but no dice: I crashed into one of them (albeit not at speed). I apologized profusely, indicating they were in the way. He was a middle-aged man, a cockney Brit, possibly the same guy as before. And he was having none of it. He cussed, swore at me, fulminated with rage.

“Come on, we’re on vacation,” I offered. This only seemed to make him angrier – so much so that skiers around him began to look askance.

“It wasn’t your fault!” said a pleasant young lady beside me, German accent. She was right, of course, but somehow it failed to soothe me. I rode the gondola a smidge down to the village (I’d had enough of riding after all this), and mused about this whole affair on the walk back.

On top of killer snow and mountain-town authenticity (and great eating), I’d come here hoping for more congenial experiences than I’d sometimes encountered at similar such American spots (see my previous post for specifics). Indeed, even with the dour Swiss I’d found a general courtesy; when people got pissy, they did so in a reserved, guarded fashion. But this explosion of rage I’d experienced harkened back to the worse of American redneckery – or, perhaps, British football hooliganism. I’d mused about such behaviors throughout my great world journey, and suspect I may have run afoul of it here. And money these days doesn’t always translate into good behavior… heck, has it ever?

Or maybe I’m just overthinking it all. Lord knows I’ve been guilty of that in the past.

After relaxing at the hotel and taking care of a few packing-related logistics, I opted to treat myself after this end-of-day turnabout: I’d already enjoyed a myriad of Swiss and Italian dishes in my time here, but have never before tried another variant of fondue, that involving meat. Calling it “fondue” is probably a bit of a stretch – although the principle of dipping stuff in a hot liquid still applies, here you boil raw shavings of beef and lamb in flavored oil, and apply dipping sauces to it. Still, it was fantastic, and capped off my time in this town very nicely.

After relaxing at the hotel and taking care of a few packing-related logistics, I opted to treat myself after this end-of-day turnabout: I’d already enjoyed a myriad of Swiss and Italian dishes in my time here, but have never before tried another variant of fondue, that involving meat. Calling it “fondue” is probably a bit of a stretch – although the principle of dipping stuff in a hot liquid still applies, here you boil raw shavings of beef and lamb in flavored oil, and apply dipping sauces to it. Still, it was fantastic, and capped off my time in this town very nicely.

I wandered through Bahnhofstrasse once last time, drinking in the lit-up shops and weekend crowds just beginning to arrive for their snow holidays. The past couple of days have given me a veritable banquet for thought, most especially about this part of the world so connected to yet still quite distinct from North America.

Since rediscovering the Continent as an adult on my great world trip, I’ve had a tendency to mythologize it: its lifestyles and social benefits; its speedy trains; its top-notch (and better-priced) mobile phone service; its populace seemingly less agro than the martial-oriented Yanks back home. But maybe it’s important for me to be jolted back to reality once in a while – on this trip, all of those elements failed in some way. No, Europe isn’t perfect… and coming here for the third time in three years offered me – in addition to splendid sights and remarkable attractions – an object lesson that, even if a place doesn’t live up to some mythic standard, it’s still capable of delivering a legendary time, and experiences that stay with you all your life.

Since rediscovering the Continent as an adult on my great world trip, I’ve had a tendency to mythologize it: its lifestyles and social benefits; its speedy trains; its top-notch (and better-priced) mobile phone service; its populace seemingly less agro than the martial-oriented Yanks back home. But maybe it’s important for me to be jolted back to reality once in a while – on this trip, all of those elements failed in some way. No, Europe isn’t perfect… and coming here for the third time in three years offered me – in addition to splendid sights and remarkable attractions – an object lesson that, even if a place doesn’t live up to some mythic standard, it’s still capable of delivering a legendary time, and experiences that stay with you all your life.

Tags:

San Miguel de Cozumel, Dec 23-25, 2012

San Miguel de Cozumel, Dec 23-25, 2012 I have to admit, some of my foot dragging on visiting North America’s third country was due to lingering preconceptions: In his book Smile When You’re Lying (a very edifying exposé of the business of travel writing), author Chuck Thompson ponders “Why Latin America Isn’t the World’s Number-One Tourist Destination (and Probably Never Will Be),” citing American mythology about rampant kidnappings, Montezuma’s Revenge, and “hey gringo” ripoff-ery.

I have to admit, some of my foot dragging on visiting North America’s third country was due to lingering preconceptions: In his book Smile When You’re Lying (a very edifying exposé of the business of travel writing), author Chuck Thompson ponders “Why Latin America Isn’t the World’s Number-One Tourist Destination (and Probably Never Will Be),” citing American mythology about rampant kidnappings, Montezuma’s Revenge, and “hey gringo” ripoff-ery. I, meanwhile, seem to have hit the flashpacker jackpot once more: Casa Mexicana, a vaguely nautical-looking, newish hotel right in the center of San Miguel, offered that great blend of comfortable and casual (and reasonable) I’d sought out on my global trek. A second-floor terrace offered a stellar view of blue seas, the town’s “Malecón” oceanfront promenade, and myriad ferries and cruise ships coming and going. Although it got put on the travel map some three decades past thanks to its dive spots – the island sits right on the second-largest reef system in the world, after Australia’s Great Barrier – it’s perhaps best known to many as a cruise port of call (for better or worse).

I, meanwhile, seem to have hit the flashpacker jackpot once more: Casa Mexicana, a vaguely nautical-looking, newish hotel right in the center of San Miguel, offered that great blend of comfortable and casual (and reasonable) I’d sought out on my global trek. A second-floor terrace offered a stellar view of blue seas, the town’s “Malecón” oceanfront promenade, and myriad ferries and cruise ships coming and going. Although it got put on the travel map some three decades past thanks to its dive spots – the island sits right on the second-largest reef system in the world, after Australia’s Great Barrier – it’s perhaps best known to many as a cruise port of call (for better or worse). “For better or worse” seems to mean that the island does indeed possess what I feared: piles of restaurants and shops geared at the cruising set that would not feel out of place in a mall in Iowa. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not one of those backpacking purists who fetishizes “authenticity” at the expense of everything else; and I’m acutely aware that “live like a local” tourism is just as much “tourism” as those loud-shirted cruisers at Carlos ‘n Charlie’s.

“For better or worse” seems to mean that the island does indeed possess what I feared: piles of restaurants and shops geared at the cruising set that would not feel out of place in a mall in Iowa. Don’t get me wrong, I’m not one of those backpacking purists who fetishizes “authenticity” at the expense of everything else; and I’m acutely aware that “live like a local” tourism is just as much “tourism” as those loud-shirted cruisers at Carlos ‘n Charlie’s. A home-cooked meal for dinner that night and a lazy day at the condo pool (and adjoining reef-let) made for a splendid Christmas Eve and Day. Festivus in the tropics is always a nice change, but for my family the venue change had broader significance: my parents’ anniversary was December 24th, and although we’d agreed not call too much attention to it, inevitably talk shifted to my father’s passing this past summer. We’re all still reeling from the aftermath of his sudden cardiac arrest on a warm July morning in Montreal. Perhaps it’s fitting, being here in the Mayan heartland just days after their calendar cycle ran out (though the assumption that this meant the end of the world was, of course, totally off the mark); for them (well, those that remain from that once-great civilization), and for us, 2012 signifies not only endings but also new beginnings.

A home-cooked meal for dinner that night and a lazy day at the condo pool (and adjoining reef-let) made for a splendid Christmas Eve and Day. Festivus in the tropics is always a nice change, but for my family the venue change had broader significance: my parents’ anniversary was December 24th, and although we’d agreed not call too much attention to it, inevitably talk shifted to my father’s passing this past summer. We’re all still reeling from the aftermath of his sudden cardiac arrest on a warm July morning in Montreal. Perhaps it’s fitting, being here in the Mayan heartland just days after their calendar cycle ran out (though the assumption that this meant the end of the world was, of course, totally off the mark); for them (well, those that remain from that once-great civilization), and for us, 2012 signifies not only endings but also new beginnings.